See Details 2016 Bliss Family Vineyards Estate Chardonnay

| Wine region | |

View of Chablis, Burgundy, from the north, vineyard of Vaulorent in the foreground | |

| Type | Appellation d'origine contrôlée |

|---|---|

| Twelvemonth established | 1938 |

| Land | France |

| Part of | Burgundy |

| Total area | 6,834 hectares (16,890 acres) |

| Size of planted vineyards | 4,820 hectares (11,900 acres) |

| Varietals produced | Chardonnay (Beaunois) |

The Chablis (pronounced [ʃabli]) region is the northernmost vino district of the Burgundy region in France. The cool climate of this region produces wines with more acidity and flavors less fruity than Chardonnay wines grown in warmer climates. These wines ofttimes have a "flinty" note, sometimes described every bit "goût de pierre à fusil" ("tasting of gunflint"), and sometimes as "steely". The Chablis Appellation d'origine contrôlée is required to use Chardonnay grapes solely.

The grapevines around the boondocks of Chablis make a dry out white vino renowned for the purity of its aroma and taste. In comparison with the white wines from the rest of Burgundy, Chablis wine has typically much less influence of oak. About basic Chablis is unoaked, and vinified in stainless steel tanks.

The amount of barrel maturation, if whatsoever, is a stylistic choice which varies widely amid Chablis producers. Many Grand Cru and Premier Cru wines receive some maturation in oak barrels, simply typically the fourth dimension in barrel and the proportion of new barrels is much smaller than for white wines of Côte de Beaune.[1]

Location [edit]

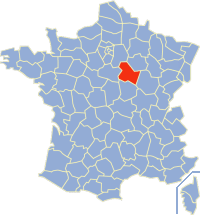

The Yonne department where Chablis is located

Chablis lies most x miles (sixteen km) eastward of Auxerre in the Yonne department, situated roughly halfway between the Côte d'Or and Paris. Of French republic's vino-growing areas, only Champagne, Lorraine and Alsace have a more northerly location. Chablis is closer to the southern Aube district of Champagne than the remainder of Burgundy.

The region covers 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) × 20 kilometres (12 mi) across 27 communes located forth the Serein river. The soil is Kimmeridge Clay with outcrops of the aforementioned chalk layer that extends from Sancerre up to the White Cliffs of Dover, giving a name to the paleontologists' Cretaceous period. The Grands Crus, the best vineyards in the area, all lie on a unmarried, small-scale slope, facing southwest and located only north of the boondocks of Chablis.[2]

History [edit]

During the Middle Ages the Catholic Church building, specially Cistercian monks, became a major influence in establishing the economic and commercial interest of viticulture for the region.[1] Pontigny Abbey was founded in 1114, and the monks planted vines along the Serein.[3] Anséric de Montréal gave a vineyard at Chablis to the Abbey in 1186.[4] In 1245 the chronicler Salimbene di Adam described a Chablis wine.[5] Chardonnay is believed to have starting time been planted in Chablis past the Cistercians of Pontigny Abbey in the 12th century, and from in that location spread south to the residuum of the Burgundy region.[6]

The Chablis area became part of the Duchy of Burgundy in the 15th century.[7] At that place are records in the mid-15th century of Chablis vino being shipped to Flanders and Picardy. But in Feb 1568 the town was besieged by the Huguenots, who burned part of it.[eight]

The development of the French railway arrangement opened up the Parisian market to wine regions beyond the country, dealing a meaning blow to the monopoly held by the Chablis vino industry at the time.

The Seine river, hands accessible via the nearby Yonne river, gave the Chablis wine producers a near monopoly on the lucrative Parisian market. In the 17th century, the English language discovered the vino and began importing big volumes.[2] By the 19th century there were nearly 98,840 acres (forty,000 ha) of vines planted in Chablis with vineyards stretching from the town of Chablis to Joigny and Sens along the Yonne. Some Champagne producers used Chablis as a basis for a sparkling cuvée.[1]

With the French Revolution, the monastic vineyards became biens nationaux, and were auctioned off. The new owners were mostly local, and the political upheaval saw small farmers involved every bit part-time vignerons. The English marketplace continued to prosper.[ix] The 19th-century Russian novel Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy mentions "classic Chablis" as a commonplace choice of vino.[ten]

The end of the 19th century was a difficult time for the Chablis growers. Firstly, with new railway systems linking all parts of the country with Paris, there was inexpensive wine from regions in the Midi that undercut Chablis. The vineyards were afflicted by oidium from 1886, and then phylloxera from 1887. Constructive replacement of vinestocks to counter phylloxera took some 15 years.[eleven] Many Chablis producers gave upward winemaking, the acreage in the region steadily declining throughout much of the early 20th century. Past the 1950s there were only ane,235 acres (500 ha) of vines planted in Chablis.[1]

The 1000 Cru vineyards of Chablis. From left to correct: Les Preuses, Vaudésir, Grenouilles (around the house), Valmur, Les Clos, Blanchots and in the far distance across the Vallée de Brechain, the Premier Cru of Montée de Tonnerre

The 20th century did bring almost a renewed commitment to quality product and ushered in technological advances that would allow viticulture to exist more than profitable and reliable in this cool northern climate. In 1938, the Institut National des Appellations d'Origine created the Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) region for Chablis that mandated the grape variety (Chardonnay) and acceptable winemaking and viticultural practices within delineated boundaries. 1 of the objectives of the AOC establishment was to protect the name "Chablis", which by this time was already existence inappropriately used to refer to just about any white wine made from any number of white grape varieties all across the world. In the early on 1960s, technological advances in vineyard frost protection minimized some of the risk and financial cost associated with variable vintages and climate of Chablis. The worldwide "Chardonnay-blast" of the mid-tardily 20th century, opened up prosperous worldwide markets to Chablis and vineyard plantings saw a catamenia of steady increase. By 2004, vineyard plantings in Chablis reached a footling over 10,000 acres (4,000 ha).[ane]

Climate and geography [edit]

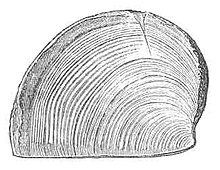

All of Chablis' G Cru vineyards and Premier Cru vineyards are planted on primarily Kimmeridgean soil which is equanimous of limestone, clay and fossilized oyster shells (pictured).

Located in northeast France, the Chablis region is considered the northernmost extension of the Burgundy wine region merely it is separated from the Côte d'Or by the Morvan hills, with the main Burgundian winemaking town of Beaune located more 62 miles (100 km) away. This makes the region of Chablis relatively isolated from other winemaking regions with the southern vineyards of the Champagne in the Aube department being the closest winemaking neighbor.[1]

The Chablis wine region has much in common with Champagne province, when it comes to climate.[12] Information technology has a semi-continental climate without maritime influence. The tiptop summertime growing season can be hot; and wintertime tin can exist long, cold and harsh, with frosty conditions lasting to early on May. Years that feel too much rain and depression temperature tend to produce wines excessively loftier in acerbity and fruit that is too lean to support information technology. Vintages that are exceedingly warm tend to produce fat, flabby wines that are too low in acidity.[7] Frost can be countered by heaters, and aspersion by sprinklers to class an water ice layer. The exceptionally poor 1972 Chablis suffered frost at vintage time.[thirteen]

The region of Chablis lies on the eastern edge of the Paris Basin. The region'due south oldest soil dates dorsum to the Upper Jurassic historic period, over 180 one thousand thousand years ago and includes a vineyard soil blazon that is calcareous, and known equally Kimmeridge Dirt. All of the Chablis Grand Cru and Premier Cru vineyards are planted on this primarily Kimmeridgean soil, which imparts a distinctively mineral, flinty note to the wines. Other areas, specially most of the Petit Chablis vineyards, are planted on slightly younger Portlandian soil, still of similar structure.[2] The chalk mural resembles some areas of Champagne and Sancerre.[14]

Viticulture [edit]

A serious viticultural concern for Chablis vineyard owners is frost protection. During the bud break flow of a grapevine's annual cycle, the Chablis region is vulnerable to springtime frost, from March to early May, which can compromise the crop yield. Formerly, the fiscal risk involved saw many producers turn to polyculture agronomics, pulling up vineyards to constitute alternative crops.[1] The 1957 vintage was striking specially difficult by frost damage: the regional government reported that only 11 cases (132 bottles) of vino were produced.[15]

In the 1960s, technological advances in frost protection introduced preventive measures, such every bit smudge pots and aspersion irrigation to the region. Smudge pots piece of work by providing direct oestrus to the vines while aspersion involves spraying the vines with h2o every bit soon every bit temperatures hit 32 °F (0 °C) and maintaining persistent coverage. The water freezes on the vine, shielding it with a protective layer of ice that functions igloo-style, retaining estrus within the vine. While toll is a factor in using smudge pots, there is a run a risk to the aspersion method if the constant sprinkling of water is interrupted of causing worse damage to the vine.[i] In that location is no such protection against hail, which in 2016 caused serious difficulties for some Chablis vignerons.[16]

At harvest fourth dimension, AOC regulations stipulate grapes for Chiliad Cru vineyard must be picked with a potential alcohol level of at least xi percent, at least x.v percentage for Premiers Crus and 9.v percent for AOC Chablis vineyards. Yields in Grands Crus must be express to 3.3 tons per acre (45 hectoliters per hectare) with a 20% allowance for increased yields.[17] At that place is no official regulation on the use of mechanical harvesting, but nearly Grand Cru producers prefer hand picking because homo pickers tend to exist more fragile with the grapes and tin distinguish better between ripe and unripe bunches. Over the residue of the Chablis region, mechanical harvesting was used by around 80% of the vineyards at the turn of the 21st century.[eighteen] The traditional way of vine training in Chablis is to have the vine trained low to the basis for warmth with four cordons stretching out sideways from the trunk.[15]

Winemaking [edit]

The 20th century saw many advances in winemaking engineering and practices—peculiarly the introduction of temperature-controlled fermentation and controlled inducing of malolactic fermentation. One winemaking event that is still contested in the region is the utilize of oak. Historically Chablis was aged in sometime wooden feuillette barrels that were essentially neutral: they did not impart the feature oak flavors (vanilla, cinnamon, toast, coconut, etc.) that are today associated with ageing a vino in barrels. Hygiene was hard to control with these older barrels, and they could develop faults in the vino, including discoloration. These old barrels fell out of favor, replaced by stainless steel fermentation tanks which also controlled temperatures.[2]

A glass and bottle of Chablis

The use of oak became controversial in the Chablis when some winemakers in the late 20th century went dorsum to wooden barrels in winemaking, using oak barrels. So-chosen "traditionalist" winemakers dismissed the usage of oak as counter to the "Chablis style" or terroir, while "modernist" winemakers embrace its use though not to the extent of a "New World" Chardonnay.[2] The amount of char in oak barrels used in Chablis is ofttimes depression, which limits the "toastiness" that is perceived in the wine.[one]

Rarely will a producer use oak for both fermentation and maturation. Grand Cru and Premier Cru wines are nearly likely to see oak: proponents believe that they have necessary structure and plenty excerpt to avoid being overwhelmed by oak influence. While there are fashion differences amongst producers, rarely is basic AOC Chablis or Petit Chablis oaked.[ane]

While chaptalization was widely practiced for most of the 20th century, there has been a trend of riper vintages in recent years, producing grapes with higher sugar levels that have diminished the need to chaptalize.[fifteen]

Appellation and classification [edit]

Map showing the location of the Yard Crus of Chablis

The main Chablis Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée was designated on Jan thirteen, 1938, but the junior appellation of Petit Chablis was non designated until January 5, 1944. All the vineyards in Chablis are covered past 4 appellations with unlike levels of classification, reflecting all-important differences in soil and slope in this northerly region. At the peak of the classification are the seven Grand Cru vineyards, which are all located on a single hillside near the boondocks of Chablis. Second in quality are the Premier Cru vineyards, which numbered 40 at the turn of the 21st century, covering an surface area of 1,853 acres (750 ha). Next is the generic AOC Chablis which, at 7,067 acres (2,860 ha), is the largest appellation by far in the region and the 1 exhibits the most variability between producers and vintages. At the lowest end of the nomenclature is "Petit Chablis" which includes the outlying land. As of 2004, one,380 acres (560 ha) of a permitted 4,448 acres (1,800 ha) in the Petit Chablis appellation was planted.[i]

Soil and slope plays a major role in delineating the quality differences. Many of the Premier Crus, and all the Chiliad Crus vineyards, are planted along the valley of the Serein river as it flows into the Yonne. The Grand Crus and some of the most highly rated Premiers Crus (Mont de Milieu, Montée de Tonnerre, Fourchaume) are located on southwest facing slopes; these receive the maximum amount of sunday exposure. The rest of the Premiers Crus are on southeast facing slopes.[12] [nineteen]

Chablis Grands Crus [edit]

In that location are seven officially delineated Grand Cru climats, covering an area of 247 acres (100 ha), all located on one southwest facing hill overlooking the town of Chablis at elevations between 490–660 feet (150–200 metres). Ane vineyard in that location, La Moutonne, between the G Cru vineyards of Les Preuses and Vaudésir, is often considered an "unofficial" G Cru.[one] [20] The Bureau Interprofessionnel des Vins de Bourgogne (BIVB) does recognize La Moutonne, but the seven Grand Cru vineyards officially recognized past the INAO are (from northwest to southeast): Bougros, Les Preuses, Vaudésir, Grenouilles, Valmur, Les Clos and Blanchot.[21] Together, the Grand Cru vineyards account for around 3% of Chablis annual yearly production.[22]

While the producer can have a marked influence, each of the Grand Cru vineyards is noted for its detail terroir feature. Tom Stevenson notes that Blanchot produces the nearly delicate wine with floral aromas; Bougros is the least expressive but nonetheless has vibrant fruit flavors; Les Clos tends to produce the almost complex wines with pronounced minerality; Grenouilles produces very aromatic wines with racy, elegance; the Les Preuses vineyard receives the most sun among the Grand Crus and tends to produce the most full bodied wines; Valmur is noted for its polish texture and aromatic bouquet; Vaudésir tends to produce wines with intense flavors and spicy notes.[12] Of all the One thousand Cru vineyards Les Clos is the largest in expanse at 61 acres (25 ha). Hugh Johnson describes the wines from this Grand Cru as having the all-time ageing potential among Chablis and developing Sauternes-similar aromas later on some bottle historic period.[22]

The Wedlock des Grands Crus de Chablis (UGCC) was launched in March 2000, as a syndicate restricted to M Cru proprietors, with mission "to defend and promote the quality of Chablis G Cru wines". Members are jump to bide by a lease which covers vino making and sales. G Cru makers must submit their wines to a tasting committee of other Matrimony members to ensure they see the required quality. These tastings are conducted bullheaded.[23]

Premiers Crus [edit]

At the plough of the 21st century, there were 40 Premier Cru vineyards. The names of many of these vineyards do not appear on vino labels. The INAO permits the use of "umbrella names": smaller, lesser known vineyards are allowed to use the name of a nearby more famous Premier Cru vineyard. Some of the "umbrella" vineyards are Mont de Milieu, Montée de Tonnerre, Fourchaume, Vaillons, Montmains, Beauroy, Vaudevey, Vaucoupin, Vosgros, Les Fourneaux, Côte de Jouan and Les Beauregards.[1] In general, Premier Cru wines have at least half a degree less alcohol by volume and tend to have less aromatics and intensity in flavors.[22]

Grapes and vino [edit]

Chablis is characterized by its pale yellowish color with greenish tint.

All Chablis is made 100% from the Chardonnay grape. Some wine experts, such as Jancis Robinson, believe that the wine from Chablis is one of the "purest" expressions of the varietal graphic symbol of Chardonnay, because of the simple style of winemaking favored in this region. Chablis winemakers want to emphasize the terroir of the calcareous soil and cooler climate that help maintain high acidity. Chablis wines are characterized by their greenish-yellow color and clarity. The racy, green apple tree-like acidity is a trademark of the wines and can be noticeable in the bouquet. The acidity tin can mellow with age and Chablis are some of the longest living examples of Chardonnay.[24] The wines often have a "flinty" notation, sometimes described as "goût de pierre à fusil" (gunflint) and sometimes every bit "steely". Some examples of Chablis can have an bawdy "wet stone" flavor that intensifies as information technology ages, earlier mellowing into delicate honeyed notes.[25] Like virtually white Burgundies, Chablis can do good from some canteen historic period. While producers' styles and vintage tin play an influential role, M Cru Chablis can generally historic period for well over xv years while many Premiers Crus will age well for at least x years.[ane]

Secondary grape varieties grown locally are permitted in the generic Bourgogne AOC wine. These include Aligoté, César, Gamay, Melon de Bourgogne, Pinot noir, Pinot blanc, Pinot gris (known locally as Pinot Beurot), Sauvignon blanc, Sacy, and Tressot.[12]

Modern vino industry [edit]

For almost of the 20th century, Chablis wine was produced more for the export than the domestic French marketplace, which tended to favor the Côte d'Or Chardonnays. Négociants are not as influential in the Chablis wine industry equally in other areas of Burgundy. Trends towards estate bottling and co-operatives have shifted the economics towards the individual growers and producer. The La Chablisienne branch makes virtually a third of all wine produced in Chablis today.[i]

In recent years, Chablis producers have fought hard to protect the Chablis designation, using legal means to make foreign countries respect information technology. Despite a long association with Chardonnay, the wines of Chablis can be overshadowed past the New Earth expression of the varietal,[xiv] and by other Burgundian Chardonnays such as Montrachet, Corton-Charlemagne and Meursault. The wide semi-generic apply of the word "Chablis" outside of France is notwithstanding seen in describing almost any white wine, regardless of where it was made and from what grapes.[ii]

See also [edit]

- List of Burgundy Grand Crus

- List of Chablis crus

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d due east f grand h i j thousand l g due north o J. Robinson (ed) "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition pp. 148–149 Oxford University Printing 2006 ISBN 0-nineteen-860990-6.

- ^ a b c d due east f A. Domine (ed) Wine pp. 186–187 Ullmann Publishing 2008 ISBN 978-3-8331-4611-4.

- ^ Pierre Vital (1956). Les vieilles vignes de notre France (in French). Société civile d'information et d'édition des services agricoles. p. 184.

- ^ Constance Brittain Bouchard (1991). Holy Entrepreneurs: Cistercians, Knights, and Economical Exchange in 12th-century Burgundy. Cornell University Printing. p. 104. ISBN0-8014-2527-1.

- ^ Marie-Hélène BAYLAC (28 May 2014). Dictionnaire gourmand: Du canard d'Apicius à la purée de Joël Robuchon (in French). Place Des Editeurs. p. 433. ISBN978-2-258-10186-nine.

- ^ H. Johnson Vintage: The Story of Wine p. 130 Simon and Schuster 1989 ISBN 0-671-68702-6.

- ^ a b E. McCarthy & M. Ewing-Mulligan French Wine for Dummies pp. 90–93 Wiley Publishing 2001 ISBN 0-7645-5354-ii.

- ^ Rosemary George (i October 1984). The Wines of Chablis and the Yonne. Sotheby Publications. pp. 21–2. ISBN0856671797.

- ^ Rosemary George (1 October 1984). The Wines of Chablis and the Yonne. Sotheby Publications. pp. 22–3. ISBN0856671797.

- ^ s:Anna Karenina/Part One/Affiliate 10.

- ^ Rosemary George (1 October 1984). The Wines of Chablis and the Yonne. Sotheby Publications. pp. 24–vi. ISBN0856671797.

- ^ a b c d T. Stevenson "The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia" pp. 140–144 Dorling Kindersley 2005 ISBN 0-7566-1324-8.

- ^ Rosemary George (1 October 1984). The Wines of Chablis and the Yonne. Sotheby Publications. pp. 54 and 125. ISBN0856671797.

- ^ a b M. MacNeil The Wine Bible pp. 201–202 Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1-56305-434-5.

- ^ a b c M. Frank "The Repose Men of Chablis Archived 2008-11-xix at the Wayback Machine" Wine Spectator, September 20, 2008.

- ^ "Hail in Chablis vineyards adds to frost woes - Decanter". Retrieved xiii September 2016.

- ^ P. Mansson, "In Chablis, Shared Ends and Contested Ways" Archived 2004-09-11 at the Wayback Motorcar Wine Spectator, June 6, 2000.

- ^ P. Mansson "Working for Alter in Chablis" Archived 2004-08-29 at the Wayback Car Wine Spectator December xviii, 2001.

- ^ Rosemary George (1 October 1984). The Wines of Chablis and the Yonne. Sotheby Publications. p. 34. ISBN0856671797.

- ^ Ed McCarthy; Mary Ewing-Mulligan; Maryann Egan (11 August 2009). Wine All-in-One For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 179. ISBN978-0-470-55542-2.

- ^ Hanson, Anthony (2003). Burgundy. London: Mitchell Beazley. p. 199.

- ^ a b c H. Johnson & J. Robinson The World Atlas of Vino p. 76. Mitchell Beazley Publishing 2005 ISBN 1-84000-332-four.

- ^ Austen Biss, A Guide to the Wines of Chablis, Global Markets Media 2009, ISBN 978-0-9564003-0-vii.

- ^ J. Robinson Vines, Grapes & Wines pp. 106–113 Mitchell Beazley 1986 ISBN 1-85732-999-6.

- ^ J. Robinson Jancis Robinson's Wine Grade Third Edition pp. 101–106 Abbeville Press 2003 ISBN 0-7892-0883-0.

External links [edit]

- Wines of Chablis official site

- Chablis Function of Tourism

- Map of Chablis showing the One thousand Crus in red, Premier Crus in orange, standard Chablis in yellowish and Petit Chablis in pale ochre.

wilkersoncasim1999.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chablis_wine

0 Response to "See Details 2016 Bliss Family Vineyards Estate Chardonnay"

Publicar un comentario